Protection orders: a lifeline or a legal labyrinth?

For survivors of intimate partner violence and family violence, protection orders are meant to serve as a critical legal safeguard. Designed to prevent further harm, these court orders set legally enforceable boundaries between survivors and their abusers. However, for many survivors, obtaining and enforcing a protection order can feel like navigating a complex and often failing system. This article explores the obstacles survivors face in obtaining and enforcing protection orders, and what needs to change to make these mechanisms more effective in truly ensuring safety.

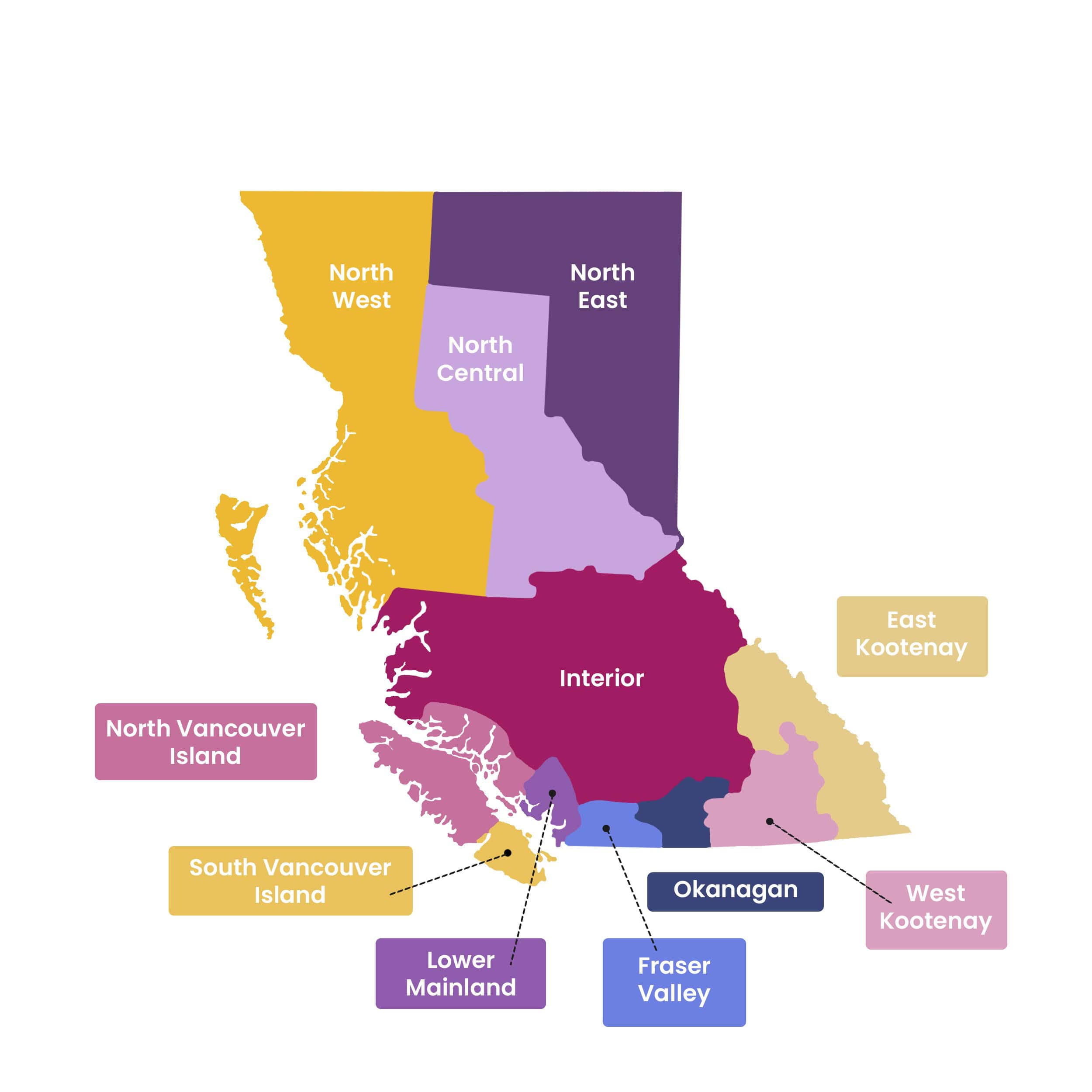

There are two primary types of protection orders in British Columbia Family Law: Protection Orders (FLPOs) and Peace Bonds. FLPOs are issued under BC’s Family Law Act and are designed to protect a person from a family member who poses a risk of violence. These orders can include restrictions on contact, proximity, and communication, and are enforceable by the police. Peace Bonds are issued under section 810 of the Criminal Code and can apply to anyone a person reasonably fears, regardless of whether they are a family member or not. Unlike FLPOs, Peace Bonds generally require Crown and police support to be pursued effectively.

While these legal tools are intended to create a sense of security for survivors and have done so for many, their effectiveness is too often undermined by systemic failures.

Barriers to Accessing and Enforcing Protection Orders and Lack of Understanding

Despite their intended purpose, protection orders are not always accessible or effective.

Many survivors, and even legal professionals, have limited knowledge of the differences between Family Law Protection Orders and Peace Bonds and the process of applying for the right terms. Rise Women’s Legal Centre states, “physical violence is heavily prioritized, while other forms of abuse are often missed or ignored”. Misinformation or lack of knowledge can lead to survivors applying for the wrong type of order, facing unnecessary delays, or struggling with enforcement when violations occur. Due to complexities and lack of consistency, survivors and support workers often do not fully understand the scope of protection these orders can offer, or their limitations. There are often process–related challenges when trying to obtain a protection order:

- Ex Parte Applications Dismissed: Survivors seeking immediate protection through ex parte (without notice) orders often face rejections without sufficient consideration of the risk involved.

- Short-Term Orders: Some protection orders are issued for only brief periods, requiring survivors to repeatedly reapply and relive their trauma.

- Misuse of Conduct Orders: Courts sometimes issue conduct orders, intended to govern behaviour, rather than full protection orders, which can leave survivors unprotected from ongoing threats. There is also a lack of uniformity in the enforcement of orders, with police action varying based on officer and jurisdiction.

When a protection order is granted, enforcement can remain a significant issue. The Rise Women’s Legal Centre notes, “The problem of enforcement does not lie solely with police; rather, it seems to be indicative of a broader disconnect between various state actors and legal professionals.” Breaches frequently do not result in criminal charges, despite the fact that violating a protection order is a criminal offence, and survivors have reported inconsistent police responses. In a survey conducted by Battered Women Support Services (BWSS), they found that “judges prioritizing the parental rights of abusive partners instead of safety of children was a barrier to successfully adding children to Protection Orders.”

Survivors are often told by police to obtain their own protection orders rather than having their cases treated as criminal matters. This shifts the burden of securing safety onto the victim rather than addressing the root cause of violence through the justice system. Furthermore, the process of obtaining a Peace Bond has become increasingly difficult, as Crown and police support is often required but not readily provided.

In their report, BWSS says, “the system for both Family Law Protection Orders and Peace Bonds is inconsistent, unsupportive and retraumatizing.” They also note that their studies show that both survivors and “to a slightly lesser extent”, workers are uninformed. Many survivors who participated in studies by BWSS and Rise Women’s Legal Centre reported feeling unsupported throughout the legal process. Some noted that their abusers used the legal system against them, such as contesting protection orders or filing retaliatory claims, to prolong control and coercion.

Additionally, survivors who face systemic barriers, including Indigenous women, trans and non-binary individuals, and racialized survivors, face unique challenges in accessing protection orders. Distrust in the legal system, fear of criminalization, and systemic biases can discourage these communities from seeking legal remedies at all.

Positive Aspects and the Potential of Protection Orders

Despite the barriers, protection orders have played an important role in safeguarding some survivors. Legal advocates acknowledge that the Family Law Act’s introduction of protection orders in 2013 was a significant improvement over previous restraining order processes. When effectively granted and enforced, these orders have helped some survivors reduce the severity and frequency of abuse. Rise Women’s Legal Centre states, “When protection order applications are successful, most survivors feel some sense of relief that the order is in place”.

Recommendations for Reform

To make protection orders more effective, systemic changes are needed. BWSS and Rise Women’s Legal Centre have proposed several key reforms:

- Enhancing Access to Protection Orders

- A specialized approach to protection orders including dedicated duty counsel to assist survivors in navigating the process, with trained anti-violence advocates or support workers.

- Extend application hours to include weekends.

- Offer virtual application options to improve accessibility.

- Strengthening Enforcement and Measures

- Improve police training on responding to protection order breaches.

- Ensure Crown prosecutors take breaches seriously and approve charges when necessary.

- Track enforcement data to ensure accountability within the legal system.

- Extend the duration of Family Law Protection Orders and Section 810 Peace Bonds to two years.

- Grant full-length Family Law Protection Orders on Without Notice applications to ensure survivor safety.

- Prioritize Child Safety in Family Law Act (FLA) Protection Order applications.

- Issuing protection orders, not conduct orders, when someone is an at-risk family member of family violence.

- Increasing Public and Professional Education

- Develop clear, accessible resources outlining the differences between Family Law Protection Orders and Peace Bonds, especially for self-represented survivors of family violence.

- Train legal professionals, police, and social workers on best practices for assisting survivors.

- Change perception on the disregard for non-physical violence and lack of understanding of risk.

- Fostering Collaboration Across Legal Systems

- Improve coordination between family law and criminal law systems.

- Create an oversight body to review protection order effectiveness and enforcement gaps.

- Specialized training in family violence.

- An immediate coroner’s inquest into any femicide death in which a protection order or peace bond was granted or sought prior to the killing.

Protection orders are a vital tool in the fight against gender-based violence, but they cannot fulfill their purpose without systemic improvements. Survivors deserve legal mechanisms that work reliably, consistently, and without placing the burden of safety solely on their shoulders.

To truly support those at risk, there must be commitment to better education, stronger enforcement, and a justice system that prioritizes survivor safety over procedural inefficiencies. Until these reforms are implemented, protection orders will remain, for too many survivors, just another piece of paper rather than a meaningful safeguard against violence.

This article has been written based on the Rise Women’s Legal Centre report, Protection Orders in BC and the Urgent Need for a Specialized Process and Coordination Reform, and the Battered Women’s Support Services (BWSS)’s report on protection orders, Justice or ‘Just’ a piece of paper?. This article uses the term “Protection Order” to specifically refer to Family Law Protection Orders.