In recent weeks, women killed by their current or former intimate partner in BC include Pamela Jarvis, a mother of six, who was murdered by her husband in Merritt in December. Early into the new year, Laura Gover-Basar, a mother of two, was killed by her ex-husband in Saanich. These are two recent intimate partner violence related deaths, but we know there are more.

In the summer there were several women killed by a current or former intimate partner in BC which included the very public murder in Kelowna of Bailey McCourt by her ex-husband. EVA BC wrote to the government then to make the point that these deaths are not one-off, isolated incidents, but part of an ongoing crisis of intimate partner violence (IPV) and violence towards women.

When a woman is killed, the trauma of her death reaches far into the community. The frontline community-based service providers who live and work in her community often end up supporting not just the survivors from the incident, but the larger community that is affected by what happens and is impacted; they also see an increase in demand for their service by survivors who may feel increased fear for their safety.

After a woman was murdered in their community, a local anti-violence agency reached out to EVA BC to share that their team was overwhelmed with requests for support from women who were being abused. This highlights again that IPV is not an isolated incident but an experience that so many women have across BC — the daily terror, fear, and stress that women have of serious injury or death happening to them, their children and/or their friends and family.

Femicides result in sharp and unexpected increases in demand for services that are difficult to manage — especially while anti-violence workers may be managing their own responses to incidents as members of the communities they serve. In some cases, they may know the victim personally or have been providing services to the victim before they were killed and be navigating a range of complex emotions.

EVA BC meets regularly with the Ministry of the Attorney General, Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General (MPSSG), Gender Equity Office (GEO), Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) and Office of the Representative for Children and Youth (RCY) to share issues that we hear from our members from the frontlines to improve a coordinated response to gender-based violence in BC. Key calls to action include the following:

- Create a standing (continuing) provincial gender-based violence death review committee.

- Strengthen cross-sector collaboration – including providing funding and support for the important coordination work already done by groups such as Interagency Case Assessment Teams (ICATS) and Violence Against Women in Relationships (VAWIR) coordination tables.

- Update the 2010 Violence Against Women in Relationships (VAWIR) policy – and create a provincial sexual assault policy.

- Provide stable, core funding to hire, retain and appropriately train community-based anti-violence support workers.

The above calls to action have been echoed by the 2025 report by legal expert Dr. Kim Stanton, The British Columbia Legal System’s Treatment of Intimate Partner Violence and Sexual Violence, commissioned by the Attorney General in 2024. Stanton’s report highlighted the long history of concerns about gaps in the legal system for cases of intimate partner violence and sexual violence, made a detailed examination of the current system and outlined clear and specific recommendations for what needs to change to increase safety for survivors and communities, and hold perpetrators accountable for their actions.

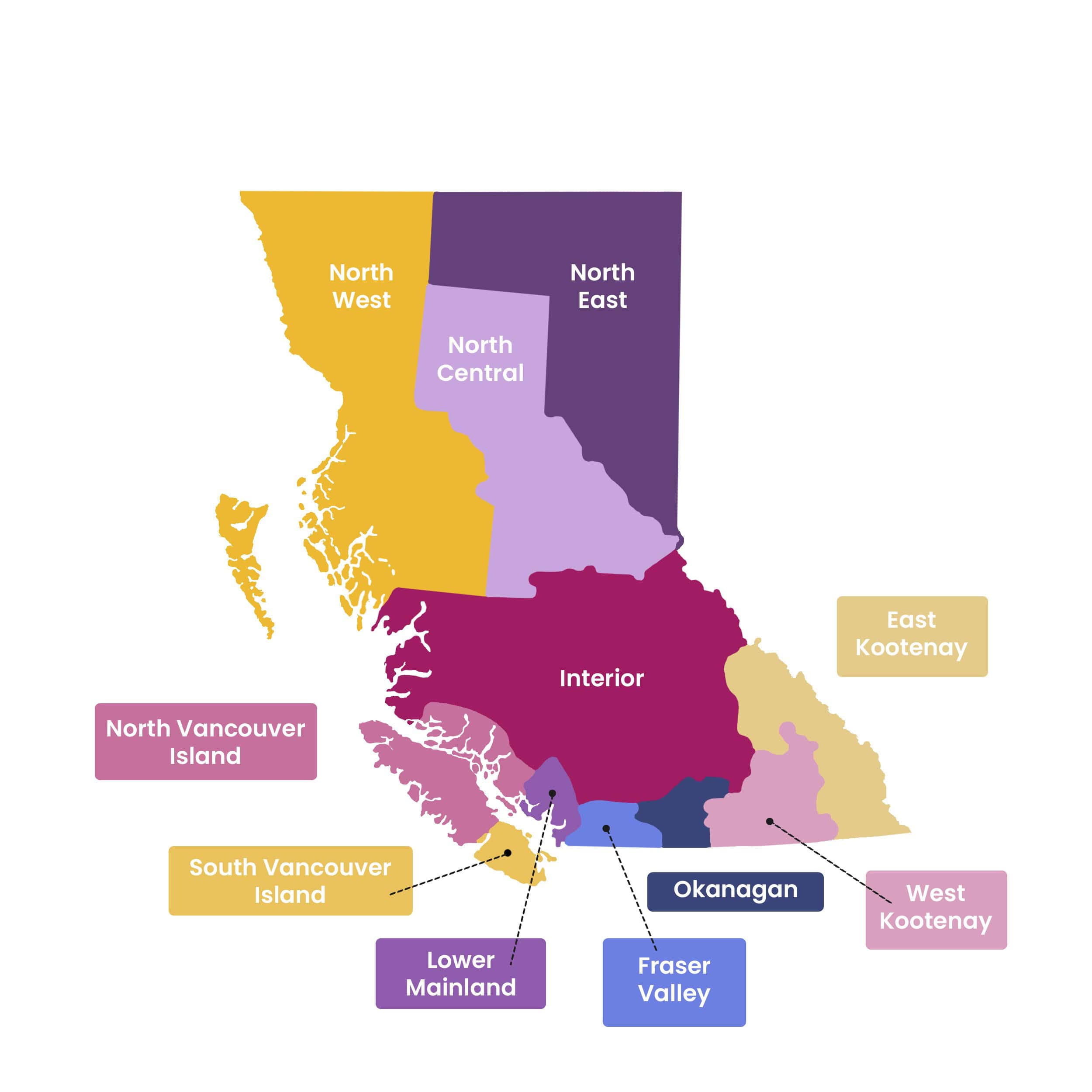

The report’s recommendations to government align with EVA BC’s advocacy priorities. Dr. Stanton notes that there is a broad consensus of the need for a “standing gender-based violence death review committee” that could play a pivotal role in closing the “critical gap in how the legal system and social services analyze, respond to, and prevent gender-based fatalities” (pg 87). Her recommendations also highlight the importance of funding ICATs in BC. EVA BC members coordinate ICATS, made up of Community-Based Victim Services (CBVS) workers, police, Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD), probation/corrections, and others who connect and support survivors of intimate partner violence. Since 2008, ICATs have worked together to respond to “highest risk cases of intimate partner violence” where there is a likely risk of “serious bodily harm or death,” and provide coordinated risk management for those cases with a priority of enhancing survivor safety. There are over 50 ICATs across BC, but there is no direct funding for this work.

Other groups that directly respond to “high-risk domestic violence” include Domestic Violence Units (DVUs) across BC. DVUs have a Community-Based Victim Services (CBVS) worker who works closely with a police officer in the local police station on high-risk cases of domestic violence. The RDVU in Victoria is one of the largest DVUs and depends on daily collaboration and information sharing with “integrated partnerships” between community partners including police departments, transition house societies, and the Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) to support survivors and ensure “safety, accountability, and meaningful change.” They report that they still often feel challenged and frustrated by a lengthy and inconsistent legal process that they note lacks an understanding about the realities of survivors’ experiences.

The provincial government has responded to Stanton’s report and expressed commitment to working with partners to address the IPV crisis and deaths. In December, Attorney General Niki Sharma announced a “comprehensive provincial framework” to guide all those within the justice system to help better respond to intimate partner violence. This announcement coincided with the federal Minister of Justice’s Bill C-16, The Protecting Victims Act that, if passed, would classify femicide as first degree murder, criminalize coercive control — a dangerous facet of intimate partner violence — and amend the definition of criminal harassment to improve the chances that a survivor who fears for their safety will be taken seriously by the justice system.

While there is a sense of movement with these new pieces of legislation, government announcements, and the ongoing dedicated work of ICATs and DVUs, the level and impact of this crisis isn’t always well understood.

It is vital that our governments give priority to action and implement the recommendations in the Stanton report, learn about the gaps in services and systems that contribute to femicides, better understand the impacts of every femicide — on the victim’s family, on anti-violence services, workers, and communities — and prevent future incidents of intimate partner homicide and femicide.

EVA BC shares heartfelt condolences to the families, loved ones, anti-violence workers and communities who supported the victims and did everything they could to keep them safe. We call on the government to act in this time of crisis of intimate partner violence in our province.