Working together to respond to highest risk cases of intimate partner violence

An Interagency Case Assessment Team (ICAT) is a formalized group made up of Community-Based Victim Services (CBVS) workers, police, Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD), probation/corrections, and others who connect and support survivors. ICATs work together to respond to “highest risk cases of intimate partner violence” where there is a likely risk of “serious bodily harm or death,” and provide coordinated risk management for those cases with a priority of enhancing survivor safety.

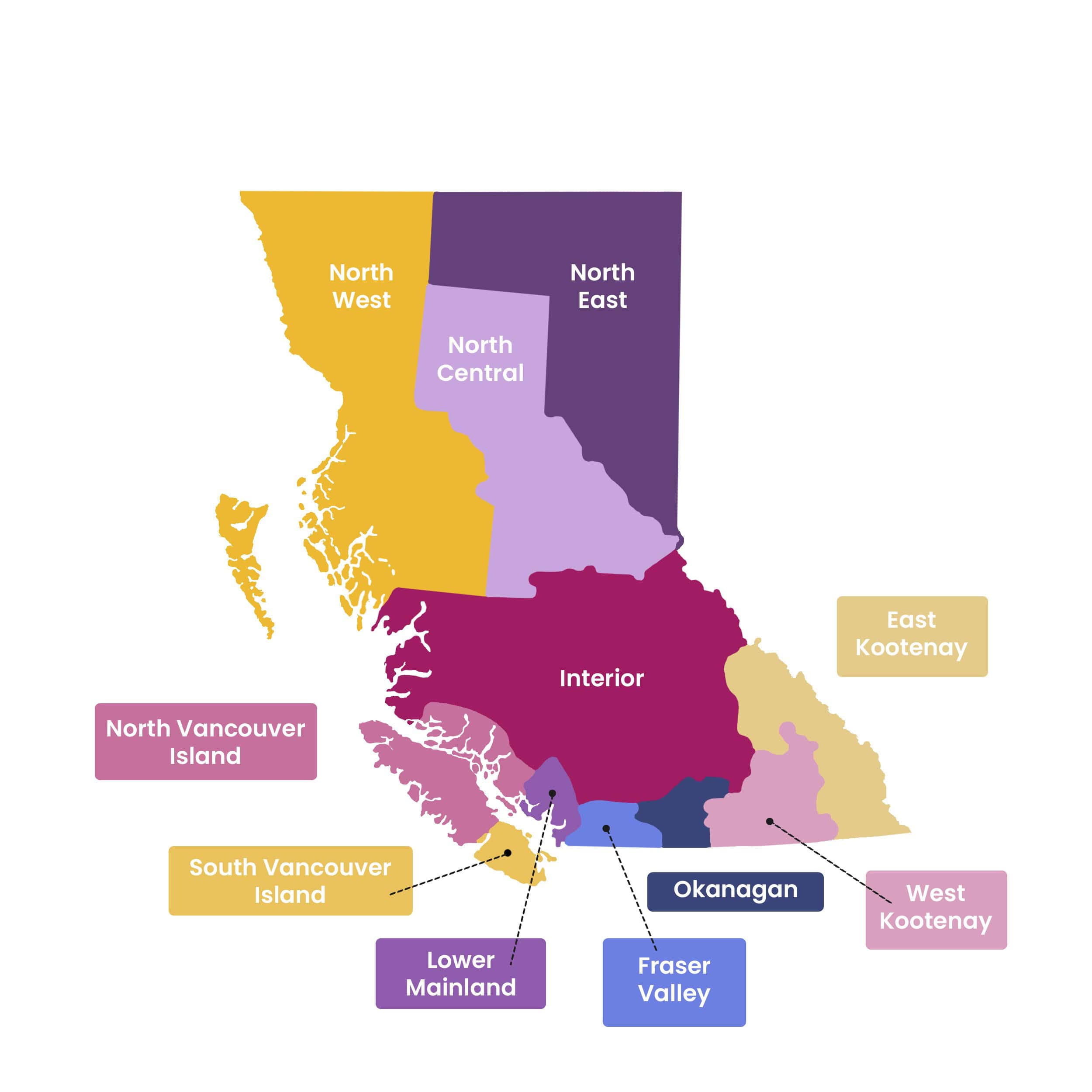

The first ICAT was created in 2008, in a collaboration between the Southeast District of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Vernon/North Okanagan Detachment, and the Vernon Women’s Transition House Society. Over the next two years, a group including the RCMP, the transition house, probation, Crown Counsel, parole, and victim services, among others, developed an ICAT model and a Memorandum of Agreement. After receiving training on risk assessment, they held the first ICAT meeting in February 2010. Meanwhile, EVA BC’s Community Coordination for Women’s Safety (CCWS) — now called Community Coordination for Survivor Safety (CCSS) — had been hearing requests for guidance on creating similar committees in communities across BC. They stepped up and, in partnership with the RCMP, began to deliver ICAT training across the province.

There are now more than 50 ICATs in BC.

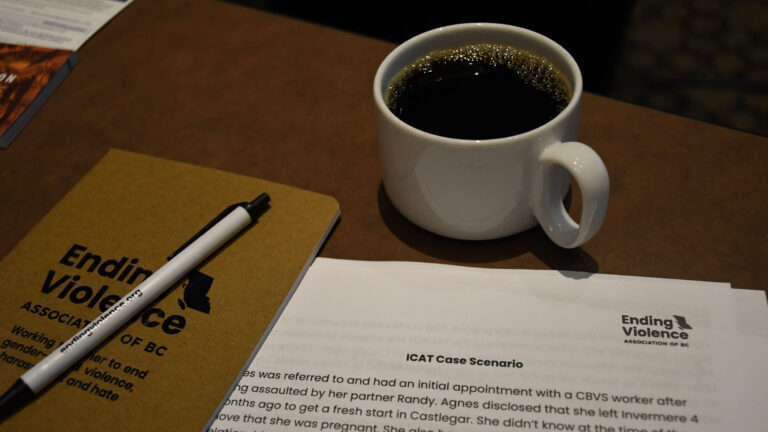

Lower Mainland ICAT training session, January 31, 2024

On January 31, 2024, Wendy Potter, EVA BC’s Director of CCSS, Kiran Toor, EVA BC’s Policy Analyst, and Sgt. Sandy Fabi of the RCMP E Division, Intimate Partner Risk Management, facilitated an all-day ICAT training session for close to 80 representatives from policing, health care, anti-violence community-based services, transition house societies, Ministry of Child and Family Development (MCFD) and corrections services in the Lower Mainland. Some who attended were already part of an ICAT or had referred cases to one; others were learning about them for the first time.

“Everyone who interacts with the survivor of intimate partner violence holds pieces of the puzzle; by coming together, we can build a more complete picture,” says Wendy Potter.

The facilitators led participants through a review of the big picture of an ICAT’s purpose in enhancing survivor safety, outlining the steps of the referral process, offering updates for those currently involved in ICATs and answering questions for newcomers. Here is some of what they learned.

Assessing intimate partner violence cases

ICAT members and agencies or individuals providing services in the community, such as counselling, can refer a case to their local ICAT.

A key tool for assessing cases referred to an ICAT is the BC Summary of Intimate Partner Violence Risk Factors (SIPVR). Participants worked in groups using the recently updated SIPVR to assess sample case studies.

The SIPVR begins with a list of evidence-based risk factors, including an escalation of abuse, coercive controlling behaviour (coercive control is a recent addition to the SIPVR and the federal government is considering adding coercive control to the Criminal Code, see Bill C-332), recent or threatened separation, threats, and strangulation.

The SIPVR also outlines documented risk factors that could put a survivor at greater risk, including the capability of the abuser to carry out threats of physical harm, or challenges and systemic barriers that impact a survivor’s ability to access support, like being a person with a disability, having a precarious immigrant status, experiencing unstable housing or living in a rural community.

A third section of the SIPVR lists risk factors based on the abuser’s history, for instance if they have mental health concerns like depression or suicidal ideation and if they have values or beliefs that support the use of violence to control the survivor. A final section considers an abuser’s access to, or threats of using, firearms or weapons, as another set of risk factors.

The SIPVR uses a red dynamite symbol to highlight risk factors that indicate an increased likelihood and severity of future violence.

At the training session, the groups using the SIPVR to decide whether a case study warranted a high-risk designation learned that the decision is not about the total number of risk factors identified, or how many have dynamite indicators. ICAT members should consider the totality of risk factors presented and incorporate the professional judgement and experience of each ICAT member when assessing designation.

ICAT review process

Once a case is reviewed to an ICAT, the ICAT follows a formal review process where all members meet to share and discuss information for each case to determine which are “highest risk”. All ICAT members take steps to ensure confidentiality and privacy as they consider each case.

While all referred cases are supported with a risk management plan for the survivor, abuser and their family, the ICAT will only continue to follow those cases designated as “highest risk.”

The day wrapped up with a more detailed review of documentation and records management requirements for all ICATs.

In addition to the formal learning, participants were able to connect and learn from each other’s experience from different communities and sectors.

Learn more about EVA BC’s work with ICATs. If your community is interested in taking part in an ICAT training session, please contact ccss@endingviolence.org.