Common Questions

Here are some common questions with answers.

General questions

I'm experiencing gender-based violence - can EVA BC help me?

Gender-based violence can take many forms, including sexual assault, intimate partner violence, harassment, and hate. If you are experiencing gender-based violence it is never your fault.

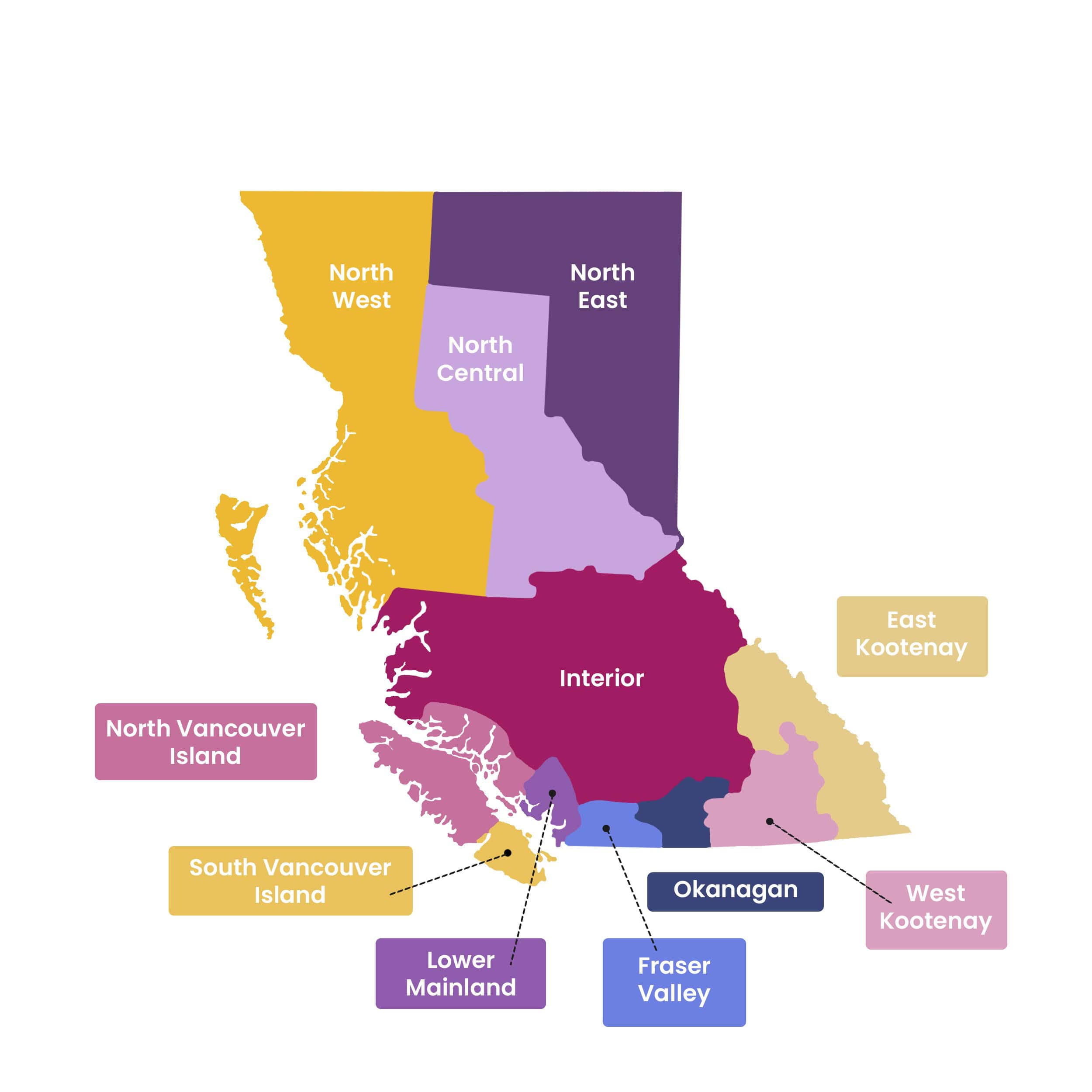

While EVA BC does not provide direct client services, you can find programs EVA BC serves that offer support and assistance with health appointments and contacting police through Community-Based Victim Services (CBVS), Stopping the Violence (STV) counselling, Multicultural Outreach and sexual violence response programs. Find a service in your area.

VictimLinkBC can also provide some confidential support and information in over 150+ languages, help you with safety planning and guide you to find services and support in your community. It is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week across BC and Yukon by phone or text at 1-800-563-0808, or by email to 211-victimlinkbc@uwbc.ca.

If you or anyone is in immediate danger, call 911 and ask for the police or paramedics.

If you are looking for transitional housing you can find a list of options and additional programs and supports through the BC Society of Transition Houses.

Statistics on gender-based violence

Here are a few statistics about gender-based violence:

How common is gender-based violence?

- More than four in ten women have experienced some form of intimate partner violence in their lifetime. Source: Statistics Canada

Who is most impacted by gender-based violence?

- There are disproportionate rates of gender-based violence. Women are violently victimized at a rate nearly double that of men. And women were five times more likely than men to be a victim of sexual assault. Other groups are also see higher rates of violence. Source: Criminal Investigation in Canada 2019

- Indigenous women and girls are 12 times more likely to be murdered or missing than any other women in Canada. Source: Reclaiming Power and Place – National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls

Questions and answers for anti-violence workers

I'm a new anti-violence worker. Where do I start to learn more and improve in my work?

EVA BC offers training and resources that can help anti-violence workers.

To get started, visit our Training Centre and Resource Centre and look for “anti-violence worker” specific options. If you work with one of our member programs, be sure to sign up for our listservs and our Program Support newsletter for important news for you including opportunities for training and access to new resources. If you have a specific question, please contact us at programsupport@endingviolence.org.

I want to know more about third-party reporting. Can you help?

- The Third Party Reporting (TPR) provincial protocol states that only workers from a CBVS program who have undergone training can help a survivor file a third party report (although there are a few STV Counselling programs who have training). Find out more here.

Common terms used

The following are a list of terms used by EVA BC and others in anti-violence work. Many of the following definitions are taken from Learning Network’s Gender-Based Violence Terminology, a glossary developed by Western University’s Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children.

Others are from the Justice Institute of BC and the SOAR Project – Supporting Survivors of Abuse and Brain Injury through Research.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE)

Adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs, are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0–17 years). For example: experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; witnessing violence in the home or community; having a family member attempt or die by suicide. Also included are aspects of the child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding such as growing up in a household with: substance misuse; mental health problems; instability due to parental separation or household members being in jail or prison.” [1]

Footnotes: [1] Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Fast facts: What are adverse childhood experiences? U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/aces/about/index.html

Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) or (BI)

An acquired brain injury (ABI) or just brain injury (BI) is an alteration in brain function caused by external forces, or a reduction in oxygen supply. A concussion is a form of traumatic brain injury caused by a hard blow or jolt to the head, neck, or body that causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth.

In intimate partner violence (IPV), a concussion can happen from a variety of causes, including being:

- Punched, or hit with an object.

- Violently shaken.

- Pushed down stairs.

- Thrown out of a moving vehicle.

Brain injuries can also happen due to strangulation, which cuts off blood flow and oxygen to the brain. Nearly half of women survivors have been strangled. It’s a common cause of brain injury in intimate partner violence, and a strong indicator of future fatality.

Coercive Control

“Coercive control is an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim.” “This controlling behaviour is designed to make a person dependent by isolating them from support, exploiting them, depriving them of independence and regulating their everyday behaviour… Coercive control creates invisible chains and a sense of fear that pervades all elements of a victim’s life. It works to limit their human rights by depriving them of their liberty and reducing their ability for action.”[1]

Footnotes: From [1] Women’s Aid. (n.d.). What is coercive control?

See also: https://lukesplace.ca/coercive-control/

Community of Practice

- A community of practice (CoP) is a group of people who share a common concern, a set of problems, or an interest in a topic and who come together to fulfill both individual and group goals.

- Communities of practice often focus on sharing best practices and creating new knowledge to advance a domain of professional practice. Interaction on an ongoing basis is an important part of this.

- Many communities of practice rely on face-to-face meetings as well as web-based collaborative environments to communicate, connect and conduct community activities.

Footnotes: Retrieved from: https://www.communityofpractice.ca/

Cultural Humility

“Cultural humility is a process of self-reflection to understand personal and systemic biases and to develop and maintain respectful processes and relationships based on mutual trust. Cultural humility involves humbly acknowledging oneself as a learner when it comes to understanding another’s experience.” [1]

Footnotes: [1] First Nations Health Authority. (2016, June). Creating a climate for change cultural humility resource booklet: https://www.fnha.ca/Documents/FNHA-Creating-a-Climate-For-Change-Cultural-Humility-Resource-Booklet.pdf

Gender-Based Violence

Gender-based violence is a term that recognizes that violence occurs within the context of women’s and girl’s subordinate status in society and serves to maintain this unequal balance of power. Gender-based violence is sometimes used interchangeably with “violence against women” although the latter is a more limited concept. The United Nations (UN) defines violence against women as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivations of liberty, whether occurring in public or private life.” [1, 2] The UN also notes that “While gender-based violence can happen to anyone, anywhere, some women and girls are particularly vulnerable – for instance, young girls and older women, women who identify as lesbian, bisexual, transgender or intersex, migrants and refugees, indigenous women and ethnic minorities, or women and girls living with HIV and disabilities, and those living through humanitarian crises.” [3] The existence and impact of gender-based violence are therefore often interconnected with other systems of inequality and/or vulnerability.

Footnotes: [1] United Nations. (1993, Dec). Declaration on the elimination of violence against women. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/declaration-elimination-violence-against-women

[2] United Nations. (n.d.). Violence against women.

[3] United Nations. (n.d.). International day for the elimination of violence against women. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/en/events/endviolenceday/

Interagency Case Assessment Team (ICAT)

An Interagency Case Assessment Team (ICAT) is a partnership of local agencies, including police, anti-violence, child welfare, corrections, health and other agencies. The purpose of an ICAT is to work together to review suspected highest risk cases of intimate partner violence with the goal of increasing safety and preventing further harm and lethality.

See more about EVA BC’s work with ICATs here.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a concept and analytic framework coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw and further developed by numerous scholars, advocates, and activists. [1] “Intersectionality is a useful framework for examining how forms of privilege and disadvantage shape women’s experiences of violence and their access to resources and supports.” [2]

“Intersectionality is made up of three basic building blocks: social identities, systems of oppression, and the ways in which they intersect.

- Social Identities are based on the groups or communities a person belongs to. These groups give people a sense of who they are. For example, social class, race/ethnicity, gender, and sexual orientation are all social identities. A person is usually a member of many different groups or communities at once; in this way, social identities are multidimensional. An individual’s social location is defined by all the identities or groups to which they belong.

- Systems of Oppressions refer to larger forces and structures operating in society that create inequalities and reinforce exclusion. These systems are built around societal norms and are constructed by the dominant group(s) in society. They are maintained through language (e.g. “That’s so gay”), social interactions (e.g. “catcalling” women), institutions (e.g. when school curriculum does not acknowledge residential schools), and laws and policies (e.g. immigration policies that make it difficult for new Canadians to access health services). Systems of oppression include racism, colonialism, heterosexism, class stratification, gender inequality, and ableism.

- Social identities and systems of oppression do not exist in isolation. Instead, they can be thought of as intersecting or interacting. In other words, individuals’ experiences are shaped by the ways in which their social identities intersect with each other and with interacting systems of oppression. For instance, a person can be both black, a woman, and elderly. This means she may face racism, sexism, and ageism as she navigates everyday life, including experiences of violence.” [2]

In the case of intimate partner violence (IPV), “people of intersecting identities are affected by oppression in different ways and therefore have unique experiences of IPV and we should not assume that survivors of IPV speak with only one voice.” [3] “Intersectionality influences whether, why, how, and from whom help is sought; experiences with and responses by service

providers and justice systems; how abuse is defined; and what options seem feasible, including escape and safety concerns. Policies and programs that do not include an intersectional dimension exclude survivors of IPV who exist at points of intersection between inequalities.” [3]

Footnotes:

[1] Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist

Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of

Chicago Legal Forum. 1989, iss. 1 art. 8, pp. 139-167. Retrieved from

https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1052&context=uclf

[2] Baker, L., Lalonde, D., & Tabibi, J. (2017, December). Women, Intimate Partner Violence, &

Homelessness. Retrieved from https://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/docs/LearningNetwork-GBV-Glossary.pdf

[3] Baker, L., Etherington, N., & Barreto, E. (2015, October). Intersectionality. Retrieved from

https://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/docs/LearningNetwork-GBV-Glossary.pdf

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) (formerly sometimes called domestic violence)

“Intimate partner violence refers to physical, sexual, or psychological harm by a current or former partner or spouse and can also be called dating violence between couples who are not married.” [1]

“Intimate partner violence often occurs as physical violence. However, there are many other forms of violence or abuse, including emotional abuse, verbal abuse, sexual abuse and financial abuse. Intimate partner violence also has a criminal component, as it can involve criminal offences such as assault, uttering threats or harassment, and can even lead to homicide.” [2] “Most victims of intimate partner violence are female.” [2]

Footnotes:

[1] Public Health Agency of Canada. (2014). What is family violence? Public Health Agency of Canada. Government of Canada, Ottawa, ON.

[2] Beaupré, P. (2015). Family violence in Canada: A statistical profile, 2013. Juristat, 34, 1. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics, Statistics Canada, Ottawa, ON. Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner (SANE)

“A SANE is a nurse who is specially trained to provide comprehensive and sensitive health care for survivors of sexual assault. BCIT Forensic Health Science offers an excellent training program for nurses, please contact them directly for details.”

Footnote: See more details on BC Womens Hospital

Survivor-Centred Approach

A survivor-centred approach is one that “prioritizes the rights, needs, and wishes of the survivor.” [1] According to this approach, it is the survivor’s right to:

- “be treated with dignity and respect instead of being exposed to victim-blaming attitudes.

- choose the course of action in dealing with the violence instead of feeling powerless.

- privacy and confidentiality instead of exposure.

- non-discrimination instead of discrimination based on gender, age, race/ethnicity, ability, sexual orientation, HIV status or any other characteristic.

- receive comprehensive information to help (them) make (their) own decision instead of being told what to do.” [1]

Footnote:

[1] UN Women Virtual Knowledge Centre to End Violence against Women and Girls. (2011). Survivor-centred approach. Retrieved from http://www.endvawnow.org/en/articles/652- survivor-centred-approach.html

Third Party Reporting (TPR)

In British Columbia, Third Party Reporting (TPR) of sexual assault is a process which allows adult survivors (19 and over) to access support and to report details of a sexual offence/assault to police anonymously, through a Community Based Victim Services (CBVS) or other designated program.

See more about our Community Coordination work on TPR here.

Trauma Informed Practice (TIP)

Trauma-informed practice (TIP) focuses on integrating knowledge about how people are affected by trauma into your procedures, practices and services. It does not require you to be experts in trauma or trauma treatment, but rather, it is a way of working that emphasizes safety, trustworthiness, choice, connection, collaboration, strengths, skill building, and self-care.

Vicarious Trauma (VT)

Vicarious trauma (VT) refers to negative changes that individuals may experience as a result of being exposed to individuals who have undergone traumatic experiences. Specifically, it can “alter [one’s] beliefs regarding themselves, others, and their worldview.” [1]

“Clinicians can experience VT when exposed to their patients’ traumatic experiences which triggers negative beliefs about safety, power, independence, esteem, and intimacy. VT can also lead to ‘decreased motivation, efficacy and empathy’ (McCann & Pearlman 1990). Typically, VT develops over time as an individual is continually exposed to their clients’ experiences, and often manifests mentally while presenting as symptoms that align with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).” [1] “Vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress have many similarities and while the two terms are meant to describe different experiences, they are often used interchangeably to represent the same phenomenon. However, VT and STS represent two distinct experiences and they apply to different populations. STS can be experienced by multiple sets of individuals, while vicarious trauma applies only to those individuals in direct care positions, such as first responders, health care providers, and social workers. STS and VT can be clearly differentiated by examining the length of manifestation of these two disorders.” [1]

Footnotes:

[1] Guitar, N. & Molinaro, M. (2017) Vicarious trauma and secondary traumatic stress in health care professionals. University of Western Ontario Medical Journal. 86(2):42-3. Retrieved from https://ojs.lib.uwo.ca/index.php/uwomj/article/view/2021

Violence Against Women in Relationships (VAWIR)

Violence Against Women in Relationship (VAWIR)/Violence in Relationship (VIR) coordination initiatives are open membership groups that include service providers who work with survivors of intimate partner violence, those who work with offenders, as well as those who provide related services. These can include but are not limited to anti-violence organizations, sexual assault centres, transition houses, Indigenous organizations, police and police-based victim services, Crown Counsel, health/mental health services, offender services and Community Corrections. VAWIR/VIRs identify and address service gaps and safety needs

See more about our Community Coordination work on VAWIRs here.

Have any other questions?

If you are an anti-violence worker and have questions not answered here, please see our Anti-Violence Worker Support pages or contact us at programsupport@endingviolence.org. Or if you work on a community coordination initiative please see our Community Coordination pages or contact us at ccss@endingviolence.org. If you have a more general inquiry, please contact us at evabc@endingviolence.org.